This essay is Part One of a series. The next article “Tradition and Rationality” is now available here!

The Modern Confucian

I grew up as a modern Chinese Confucian, not identifying with a particular religion, but with a strong sense of ethics that was part of my cultural inheritance: Accept criticism with humility, respect your elders, and obey the laws of society. Although we never visited any Buddhist temples or Daoist shrines, my parents believed in an abstract notion of karma, an idea that doing evil deeds will lead to eventual negative consequences, even if no one catches you doing it. We were also far from agnostic on ethical questions. Right is right, and wrong is wrong, regardless of your own personal wishes.

Looking back, I felt that the educated Chinese, and especially my own family, were particularly distinguished from other Americans for their ability to confront the truth. The modern Confucian never allows his ego to get in the way of excellence. If someone does something better than you, you need to learn from him, without making excuses. If someone argues with you, you think about whether his criticisms are actually valid rather than dismissing his points. If someone is right, you acknowledge the truth of what he says, even if you hate him. You’re always willing to adopt the other position and think about whether you yourself could be the mistaken party. “You are just personally attacking me” is not a sentence in our vocabulary.

The combination of a competitive spirit and a zero-ego approach to self-improvement leads many Chinese people to good universities and prestigious jobs. In my case, it eventually led me to the Orthodox Christian Church.

Mere Atheism

As a teenager, I had a natural obsession for thinking about questions of right and wrong, which eventually turned into a love for philosophy. I felt that “If someone’s belief is truer than yours, then why would you keep clinging onto your previous false beliefs?” I would go on the internet and browse articles and forum comments on hot button ethical issues, like digital piracy, human rights, and drug legalization, and I would keep reading arguments until I’d decided on what seemed true to me. At the age of 13, I decided that atheism, and in fact, anti-theism, must be true, in part because modern “scientistic” atheism seemed to be so much better and more consistent than the ideology of mass-media evangelical protestants. For example, I perceived that proponents of weed legalization would say that drugs are about a man having control over his own private life, while Christian opponents would make special appeals against weed by saying that the Bible has outlawed drugs. Inspired by people like George Carlin and Richard Dawkins, I felt that Christianity must have been a man-made religion that was becoming increasingly irrelevant with the “progress” of modern science.

My beliefs began to evolve in high school, where I started taking classes on literature, European philosophy, and modern ethics. Because of my nature as an obsessive truth-seeker, I loved those classes and took them extremely seriously, taking care to engage with the subject matter deeply and contrast the ideas with my own thinking. It also helped that the classroom environment naturally incentivized me to be more sincere in my studies to get better grades. In my literature class, we were taught to read the Bible from a secular perspective “as a work of great literature,” and I was exposed to the stories of the Old Testament and the basic framework of sin and justice with the help of talented teachers who were simply trying to convey the message clearly in a neutral context. I particularly loved the early stories of Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and began to view them as beautiful myths that performed good service to early people who didn’t know any better.

After learning about the Old Testament, I began to become increasingly intolerant of modern American atheism. I now started to see that these atheists did not even have a basic understanding of the Bible, and in their blindness, would throw away the good inheritance of Christian myths without even bothering to understand them. They would ask unreasonable questions like “Why did God say ‘where art thou, Adam,’ as if He could not see?” when such basic answers were easily accessible within the source texts and with some honest critical thinking (the answer: Adam hid himself from God on purpose, on account of his own sin, and God was speaking on account of His mercy, not His inability to see). I started to see that they were not intellectually honest and were, in a way, religious themselves, defining themselves as anti-Christian rather than true atheists. Incidentally, this is why I think we must be careful when thinking about the concept of “atheism,” because in the West, it is certainly defined by opposition to Christianity, while in modern East Asia, it is more like a childlike lack of belief in religion.

Afterward, I completely disavowed modern American atheism and gave it zero intellectual respect, but I still had materialistic presumptions and did not believe in a personal God as defined by the Christians. In modern literature class, we were exposed to a wide variety of writers, and I was particularly drawn to the French existentialism of Albert Camus, who was charming and ironic, and Jean-Paul Sartre, who seemed to be a wretched over-thinker. Their writings were philosophically rich and perfectly captured the post-Christian spirit in a seductive and reasonable way. The chief idea I took away from these readings was that the human life was devoid of intrinsic meaning, but we construct myths and narratives for ourselves through a combination of personal pleasure and self-delusion. In this context, religion was like a creative fiction and a personal choice, and the wise man could still abide by religious ideas but only with an ironic sense of distance.

I also loved the writing of Hermann Hesse which perfectly appealed to modern, bourgeois, truth-seeking strugglers. His writing depicted the young man’s path of heroic transformation, the struggle of heady rationalism versus integrated consciousness, and the search for light, goodness, and authenticity in the chaos of the modern godless world. I felt drawn to his characters, as I myself was a sincere and occasionally-naïve sojourner trying to grasp onto objective truth in our slippery, rootless, and ironic society.

"Have I played my part well? Then applaud, for the comedy is over!”

- Emperor Augustus, on death

Dreams and Certainty

It was also at this time that a dear friend and classmate introduced me to Daoism, the Chinese philosophy of Lao Zi and Zhuang Zi. I learned about it seriously, for the first time, in an American context, as my parents had never passed down this tradition to me. I loved Zhuang Zi, who was playful, thoughtful, and self-consistent. He was the ultimate skeptic, much greater than Descartes and his successors, because Zhuang Zi was even skeptical of his own skepticism. He would ask not just “How do I know?” but also “How do I know that I do not know?” One of my favorite passages is his discussion on dreams and the fear of death:

How do I know that enjoying life is not a delusion? How do I know that in hating death we are not like people who got lost in early childhood and do not know the way home?

Lady Li was the child of a border guard in Ai. When first captured by the state of Jin, she wept so much her clothes were soaked. But after she entered the palace, shared the king's bed, and dined on the finest meats, she regretted her tears. How do I know that the dead do not regret their previous longing for life?

One who dreams of drinking wine may in the morning weep; one who dreams weeping may in the morning go out to hunt. During our dreams we do not know we are dreaming. We may even dream of interpreting a dream. Only on waking do we know it was a dream. Only after the great awakening will we realize that this is the great dream. And yet fools think they are awake, presuming to know that they are rulers or herdsmen. How dense! You and Confucius are both dreaming, and I who say you are a dream am also a dream. Such is my tale. It will probably be called preposterous, but after ten thousand generations there may be a great sage who will be able to explain it, a trivial interval equivalent to the passage from morning to night.

After putting my full mind into the teachings of Zhuang Zi and the European existentialists, I realized that many “certainties” of modern life — such as the idea that this world is real and not some sort of simulation — were not certain at all and were built on very flimsy epistemological foundations and limited by extremely narrow preconceptions. Even the “objective” knowledge of science depends on fundamental assumptions of cause-and-effect (it’s not obvious that an action at time T causes the effect at time T+1), the consistency of the universe (it’s not obvious that physical properties at a certain time and place should always be true for all times and all places), and the idea that your particular assignment of empirical data points to a trend line is the correct one. No one has ever “seen” the law of gravitation, and even fewer have seen the boundaries of the universe. There is not even such a thing as perfect measurement, since the act of measurement itself changes the test subject, by bombarding it with photons or by snipping away a piece of it.

What we call science is simply our best guess with the instruments we have today, and the 0.001% of measurement error hiding in a experimental process is the determinant of your own faith. Those who think that “0.001% is good enough” are the self-satisfied materialists, but those who see the limitation of this type of thinking are the true skeptics and the real scientists, like an airplane pilot who knows that one day the wings of the aircraft might fall out from under him.

Materialism and its Limits

I began to believe that reductionist materialistic atheism — the idea that all things are caused solely by physical phenomena — was itself a type of religion, and not a particularly good one. It lacked explanatory power, it wasn’t consistent with itself, and it also wasn’t faithfully followed by its practitioners. Materialist atheists would say “we’re all just a bundle of chemicals” and yet continue to love their families in all seriousness and without a hint of irony. They say things like “money is just a social construct” and yet get infuriated when you steal from them. They say they only believe in science, and yet they espouse ideas like human rights and democracy which can never be seen in the laboratory.

"There is no such thing as philosophy-free science; there is only science whose philosophical baggage is taken on board without examination.” - Daniel Dennett

Most egregiously, the materialist person, who believes that all his actions are determined by brain chemicals, has no basis by which to conclude that his actions are right. If “your” brain is just a bunch of arbitrary chemical processes, why should you trust “your brain” over someone else’s? Why is “your brain” more trustworthy than a man who walks to the beach and uses the configuration of sea-shells that wash on the shore as a basis for determining his life? Why is dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin randomly firing in all directions any better than leaves blowing in the wind? How do you know that you aren’t just a simulated brain-in-a-vat who woke up yesterday with false memories, or that your deepest feelings and emotions aren’t simply implanted by a hostile actor injecting neurotransmitters into your brain?

Reductionist materialism cannot save us because it destroys the source of all knowledge. The man who cannot trust his senses certainly cannot use those same senses to examine chemicals in a laboratory. Modern scientism tells us “man is just an animal, like the beasts,” and yet the scientist says this as if he is an angel, as if his judgment does not apply also to himself.

“A purely unsurpervised learning agent can never learn what to do, because it has no information as to what constitutes a correct action or a desirable state.” - Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig

Which Justice?

Atheists often say “You were born a Christian, so how can you judge whether it’s true?” But what they do not realize is that they, too, were born into atheism. Naturally following the spirit of the times, the precocious atheist simply reads between the lines and "rebels" against the watered-down faith handed to him by his parents. But he doesn't examine whether the times themselves are true, and whether the framework of his rebellion is even a sensible default position to take.

I first learned about the history of ideas from After Virtue, by Alasdair MacIntyre, which thoroughly discusses the problem of modern secular discourse. Most people in the modern West rely on concepts like justice, fairness, right-and-wrong, and most egregiously, “human rights,” without having a serious philosophical theory about where those concepts come from. Many people who say “That’s not fair” do so out of empty emotional sentiment, and their words are devoid of substance unless they consciously possess a consistent theory of equity.

Tracing backward from the paucity and emptiness of our modern discourse, MacIntyre talks about how the “universal secular values” of the modern world were actually birthed in the provinces of Western Europe and crafted by the hands of highly-peculiar elite scholars during the “European Enlightenment.” These scholars tried to create a world where ethics could exist without the idea of transcendent truth, without God, and in so doing, they sawed off the branches of the tree they were sitting on. Despite the philosophical inconsistency of these theories, they became very popular among nation-builders and revolutionaries who reshaped the ethics of modern Europe to suit their own beliefs and wishes. Eventually these values were exported across the entire globe, giving birth to modern atheism, and we, in America, are all the spiritual children of this small cohort of thought-leaders, even if we do not acknowledge them as our fathers.

Reading MacIntyre and tracing the history of my own beliefs was like eyesight being restored to the blind. To neglect this science, to be ignorant about one’s own unconscious metaphysical presumptions, is like taking medicine from a doctor whose credentials you've never seen. Although atheists harshly criticize Christianity as being a historically-conditioned desert religion, they fail to see that they themselves are the pious worshippers of the Post-Enlightenment Faith, which demands so much out of its believers — immolating the ideas of truth, love, and beauty on the altar of materialism — and is itself the most historically-conditioned of all.

Waking Up From the Dream

I had finally unplugged myself from the matrix of the European Enlightenment and became, for the first time, a “neutral” person with very few unexamined convictions. I didn’t want to believe in any irrational propaganda that only became popular because of arbitrary historical conditions, such as modern atheism. I wanted to be like Zhuang Zi, leaving unknowable things to be in the realm of the unknown. I still performed my duties as a son, citizen, and student, but viewed it as a “social game” that you do for enjoyment and self-benefit, as articulated by Camus and Hermann Hesse.

Within this context, I started introspecting a lot on what I truly believed and on what was precious to me. I thought about my family, whom I loved very dearly in a real way. I never thought of them as materialistic chemicals but as full-fledged human personalities who filled my life with love and happiness. When people in philosophy chats occasionally asked “Would you wipe your memories and enter a simulation that made you perfectly happy?”, I would always answer “No” because I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving my family behind in the un-simulated world of inferior happiness.

I also thought about truth, the object of my great obsessions and the whole reason I was even at this stage in my life to begin with. I didn’t think that truth was unreal. How can anyone believe that? Can we use truth to say that truth is untrue? If someone is trapped in the framework of lower understanding, isn’t it our duty to lift him up to a higher level? That was a core belief of mine, and I was unwilling to compromise that. When I thought about “Would you rather be a happy pig or a sad human?” I always chose the side of truth, even if it made me miserable, and even if it was against the ethics of brain chemicals and hedonism.

So I decided to take a leap of faith and fully believe in Love and Truth. Actually, it wasn’t a leap of faith. It was something I had believed in all along. I used my rational mind to articulate and accept the unconscious beliefs of my soul. Having thrown away the garbage of the fake intellectual inheritance of our times, I discovered the treasures of authentic belief hiding within my heart. Because of this, it became mandatory for me to seek a philosophical theory by which Love and Truth were actually coherent and meaningful ideas.

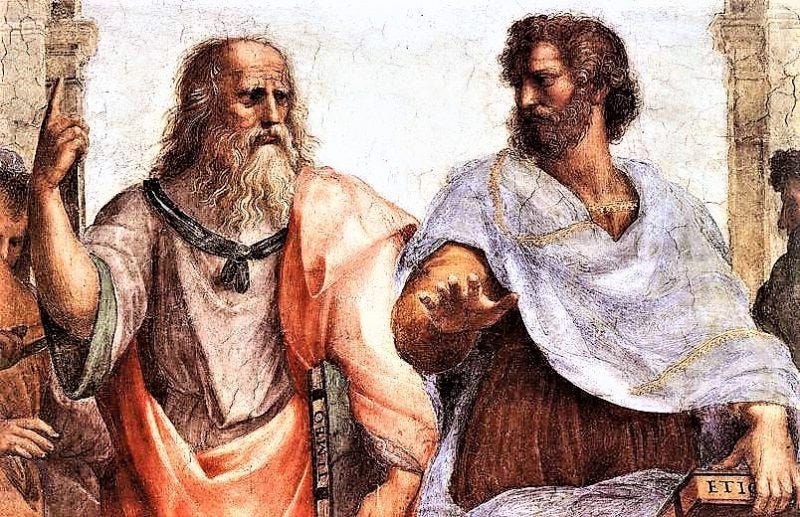

I finally became an abstract believer of a pre-Western, Greco-Chinese “religion,” where Love and Truth exist as transcendent realities beyond our material and rational world, held in place by an Absolute Idea which some people might recognize as “God.” I began reading Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics with intellectual seriousness, and felt a breath of fresh air in seeing the confidence, precision, and moral accuracy of his writing, which was overflowing with the beauty and substance of the men who lived in the world before Nietzsche said, “God is dead.”

"Beauty is the splendor of the true.” - Plato

The Empty and the All

Being an abstract “virtue believer” was an alright and decent life, but I was still curious to learn about world religions, as I no longer had a materialist basis by which to deny their validity. I studied Buddhism, Islam, Neoplatonism, and Christianity and drew inspiration from what I learned. My friend pointed me to Frithjof Schuon, a philosopher associated with the theory of “perennialism,” who argued that all orthodox, traditional religions lead to God.

“When the divine Light descends onto the human plane — embodying itself, as it were — it undergoes an initial limitation, resulting from human language and from the requirements of a given collective mentality, or cycle of humanity.”

- Frithjof Schuon

Schuon possessed everything that I needed at that point in my spiritual journey. He was very “rational” and intellectually sophisticated, but his idea of “rationality” included the supernatural world too. He differentiated the “exoteric” aspect of religion — that which seems superficial, dogmatic, particularized, and external — from the “esoteric” core — which is the intellectual, universal, and hidden truth of all religions. For example, he argued that the apparently irrational phenomenon of miracles are “inevitable” in the divine economy, since God is so vast that He eventually will pierce through our crude and mundane world simply by His nature, similar to how the geological processes of the earth eventually cause diamonds to be formed out of common carbon. Schuon also did not think that every religion was valid, but he only believed in the orthodox versions of great religions with blessed spiritual fruit that defined human civilizations.

Learning from Schuon, and also the Neoplatonic philosopher Iamblicus, I came to believe that religion was not just a common communal “activity” but a way of integrating traditional philosophy into the human life through practice. This greatly resonated with me, as I had already grown to dislike how many modern western “philosophers” had zero skin in the game of their own theories and also didn’t practice what they preached. And I was also confounded by the fact that Lao Zi and Plato wrote great treatises on the Absolute but did not actually explain the path by which an ordinary man could come to integrate the True and Beautiful in his life. Iamblichus wrote of religion as being a type of “theurgy,” where the idea of God was expressed through art, music, and ritual, and could enlighten the human soul through repeated practices. The Zen Buddhists were also particularly clear on using religious activities as spiritual “exercises,” almost like a muscle in the soul that can be trained with repeated effort.

Schuon also described how the Eucharist of the Christian faith — where bread and wine is transformed into the Body of Christ to be consumed by the faithful — was filled with deep metaphysical significance, with God, the Absolute, descending into our relativized world in order to nourish the human soul. “God became man so that man might become god.” From this, I concluded that the Christian Eucharist is itself the Elixir of Eternal Life pursued by all the great Chinese emperors.

As I learned more about the symbols and mysteries of ancient Christianity, I saw that it did not resemble at all the silly human religion that I saw in mass-media evangelicalism. Instead, I encountered a tradition with great intellectual sophistication and literary beauty. I became convinced that, without some sort of religion, we cannot truly “know” philosophy in the depths of our souls and practice it in our lives. And we need to pick a particular religion, just as a linguist must choose a particular language if he wishes to write a speech. Taking a leap of faith, this time for real, I decided to pursue Christianity… (Continued in Part Two.)

Awesome to read your story about leaving the atheist faith. It seems like Chinese people are in a better position to accept Christianity than much of the West is. Chinese people seem to be humble while the west has the issue of “me, me, me” where the individual has become their idol.

Good writing. I resonated with a lot of your own personal story despite coming from a completely different ethnic and socioreligious background. Can't wait for part 2!

I also cannot wait for you to dive more deeply into eastern philosophy and classical works, as I've had my fill of the Western classics.